Virtual Reality in Language Learning:Theory, Practice, and Future Directions

1. Background

Traditional English as a Foreign Language (EFL) instruction faces several persistent challenges that hinder learners’ communicative development:

With the advancement of technology, Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a powerful and innovative tool in language education. VR creates immersive, computer-generated environments that allow learners to interact in real time using headsets and motion-tracking devices, simulating real-life communication scenarios and enhancing learning engagement.

2 Theoretical Foundations Supporting VR in Language Education

Constructivist theory

Kolb’s experiential learning theory

Social Learning Theory

Digital experiential learning

Distributed cognition theory

Embodied cognition

Summary:

Collectively, these theories—constructivism, experiential learning, social learning, digital experiential learning, distributed cognition, and embodied cognition—provide a strong theoretical foundation for the integration of VR in language learning. They validate VR as a powerful tool for immersive, interactive, and context-rich educational experiences that support both language acquisition and learner development.

3. The current situation of VR in language learning

1) Most Common Areas of VR Application in Language Learning

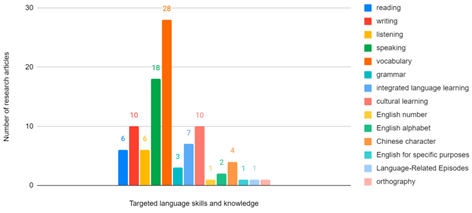

According to Huang et al. (2021), vocabulary learning was the most popular area of focus in the reviewed studies. In addition to vocabulary, VR technology was also widely used to support other aspects of language learning, including speaking, writing, cultural learning, reading, listening, integrated language learning, Chinese characters, and grammar instruction. Some studies also applied VR to teach the English alphabet.

2) Main Users of VR-ELL Systems

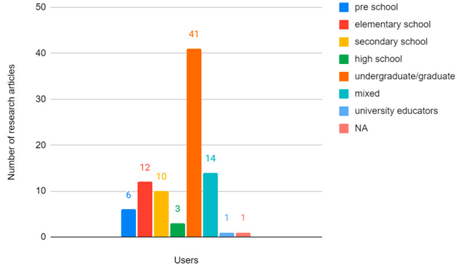

The primary users of VR-based English Language Learning (VR-ELL) systems were university and graduate students, indicating a trend toward higher education settings in adopting immersive learning technologies(Huang et al.,2021).

4. Types of VR: Low vs. High Immersion

VR experiences can be categorized by their level of immersion:

- Low-immersion VR (or desktop VR) occurs on standard computer screens without headsets, offering limited sensory engagement. (Kaplan-Rakowski & Gruber, 2019) Example: Second life. You can try it with this link https://secondlife.com/. Here is a brief introduction video on the left. The video on the right offers a scenario-based explanation of how Second Life can be used as a tool for teaching English.

- High-immersion VR involves head-mounted displays (HMDs) or room-based projection systems, allowing users to feel physically present in the virtual environment (Estes, Dailey-Hebert, & Choi, 2016; Freina & Ott, 2015). Relative tools will be introduced in the following.

5. Key Concept: Immersive Language Learning

5.1 Definition and Features

5.1 Definition and Features

Immersive learning is an instructional approach in which learners are fully engaged in simulated or real-world environments that promote natural and meaningful language use. It’s a great way to learn because it allows learners to truly experience almost all aspects of life in the language they’re learning. In the context of VR-supported language education, students can practice English in realistic virtual settings—such as cafés, airports, or classrooms—all from the comfort of their homes. These environments are characterized by:

- Active participation

- Context-rich communication

- Authentic, real-world language application

5.2 Pedagogical Value of Immersion

Immersive language learning environments expose students to the target language in authentic, contextually meaningful situations. English as a Foreign Language (EFL) immersion programs are a well-established example, having demonstrated effectiveness in promoting bilingual proficiency and academic achievement (Genesee, 1987). Students enrolled in such programs often develop strong linguistic competencies in both English and their native language (Lasagabaster & Doiz, 2016), reaping both cognitive and academic benefits through sustained exposure.

Early immersion, in particular, has been linked to notable cognitive development. As Cummins (1977, 1978) observed, students in early EFL immersion settings often exhibit enhanced executive functioning, cognitive flexibility, metalinguistic awareness, and problem-solving abilities (Baker & Wright, 2021). These advantages are not merely temporary; longitudinal studies indicate that the benefits of immersion are long-lasting, often leading to superior learning outcomes compared to non-immersion peers (Collier & Thomas, 2017).

5.3 Implications for Language Education

Beyond cognitive and academic benefits, immersion fundamentally supports the central goal of language education: developing proficiency in the target language. As Genesee (1987, p. 191) emphasizes, “second language proficiency tends to increase the earlier immersion begins and the more second language exposure the learner has.” Consequently, early total immersion programs typically produce higher levels of second language attainment than partial or delayed immersion models. Nevertheless, any form of immersive exposure is more effective than none at all.

From a pedagogical standpoint, these findings underline the importance of maximizing learners’ exposure to the target language through immersive experiences. With advancements in digital technologies, particularly Virtual Reality (VR), educators now have new tools to recreate immersive environments beyond traditional classrooms. VR allows learners to engage in meaningful, real-time interactions in lifelike settings, offering scalable and accessible opportunities to enhance second language acquisition.

6. The Educational Benefits of VR for Language Learning

Virtual Reality offers a wide range of benefits for education, particularly in the domain of language learning. Its immersive nature, combined with technological adaptability, creates rich opportunities for developing communicative competence—especially in speaking.

7. Some VR Tools

7.1 Global Platforms: ImmerseMe and Mondly VR

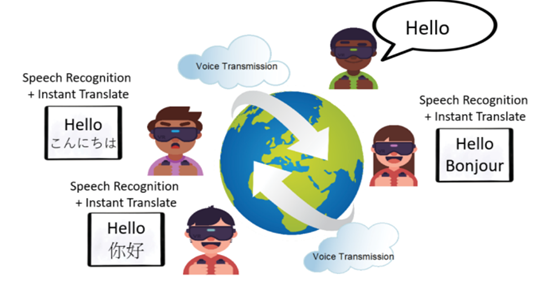

The figure illustrates the core concept behind the proposed VR-based spoken English learning platform. This system is designed to transcend traditional barriers of time and space, enabling users from around the globe to communicate and learn in real time. An integrated instant messaging system ensures seamless interaction among users, while real-time translation technology facilitates mutual understanding between speakers of different languages. This fosters a more natural and immersive second-language acquisition experience.

Several existing platforms offer similar immersive learning opportunities. For instance, ImmerseMe features over 3,000 interactive scenarios across nine languages. Learners can simulate real-world conversations in culturally authentic settings—such as ordering food in Paris or shopping in Tokyo—thus gaining contextual language skills in a practical, engaging way.

Another example is Mondly VR, which allows users to engage in dialogue with virtual characters. These interactions simulate everyday situations like ordering drinks or making introductions, helping users to improve both their speaking and listening abilities within a safe and controlled environment.

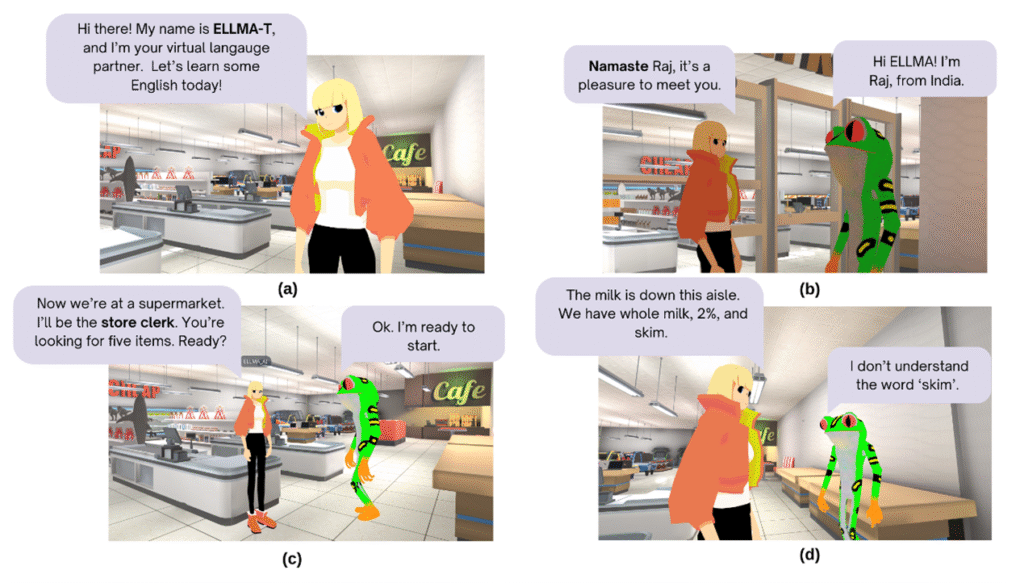

7.2 AI Integration: Personalized Learning with ELLMA-T

The development of AI-powered virtual agents such as ELLMA-T represents an innovative integration of large language models with virtual reality to deliver personalized language learning experiences. These agents are capable of assessing learners’ language proficiency and providing individualized feedback, thereby enhancing language acquisition through immersive role-plays and context-rich interactions. A teaser image illustrates ELLMA-T—an embodied conversational agent (ECA) based on GPT-4—engaged in a role-play scenario within VRChat, simulating a supermarket conversation.

A teaser image illustrates ELLMA-T—an embodied conversational agent (ECA) based on GPT-4 — engaged in a role-play scenario within VR Chat, simulating a supermarket conversation.

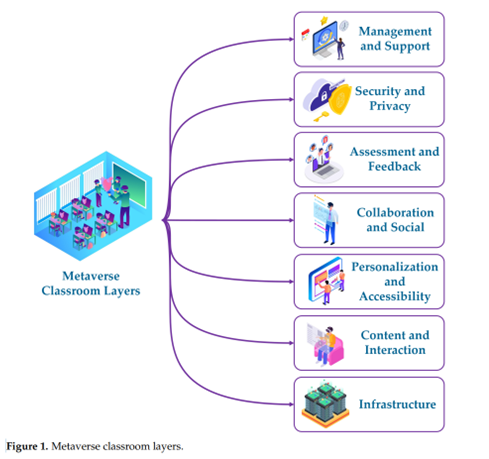

7.3 A Multi-Layered Metaverse Classroom

The Metaverse is a collective virtual space that merges physical reality with digital environments, enabling users to interact with each other and digital content through avatars in real time. It is often described as the next evolution of the internet—an immersive, 3D version of the web—where people can work, learn, socialize, shop, and play in virtual worlds that feel increasingly lifelike.

Powered by technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI), and cloud computing, the metaverse offers a seamless blend of the digital and physical worlds. Companies like Meta (formerly Facebook), Microsoft, Google, and Tencent are actively investing in metaverse-related technologies, indicating its growing importance in both consumer and professional domains.

In education, the metaverse has the potential to transform traditional learning by offering students highly immersive environments where they can participate in virtual science labs, historical reenactments, or global language exchanges. In commerce, brands are building virtual stores and hosting interactive events, while in healthcare, professionals are using VR simulations for training and therapy.

However, the development of the metaverse also raises important concerns, including data privacy, digital equity, mental health, and ethical governance. As it continues to evolve, it will require collaboration across industries and disciplines to ensure that it is inclusive, secure, and beneficial for all.

7.4 Other tools waiting for you to explore

8. Examples of VR Applications in Teaching

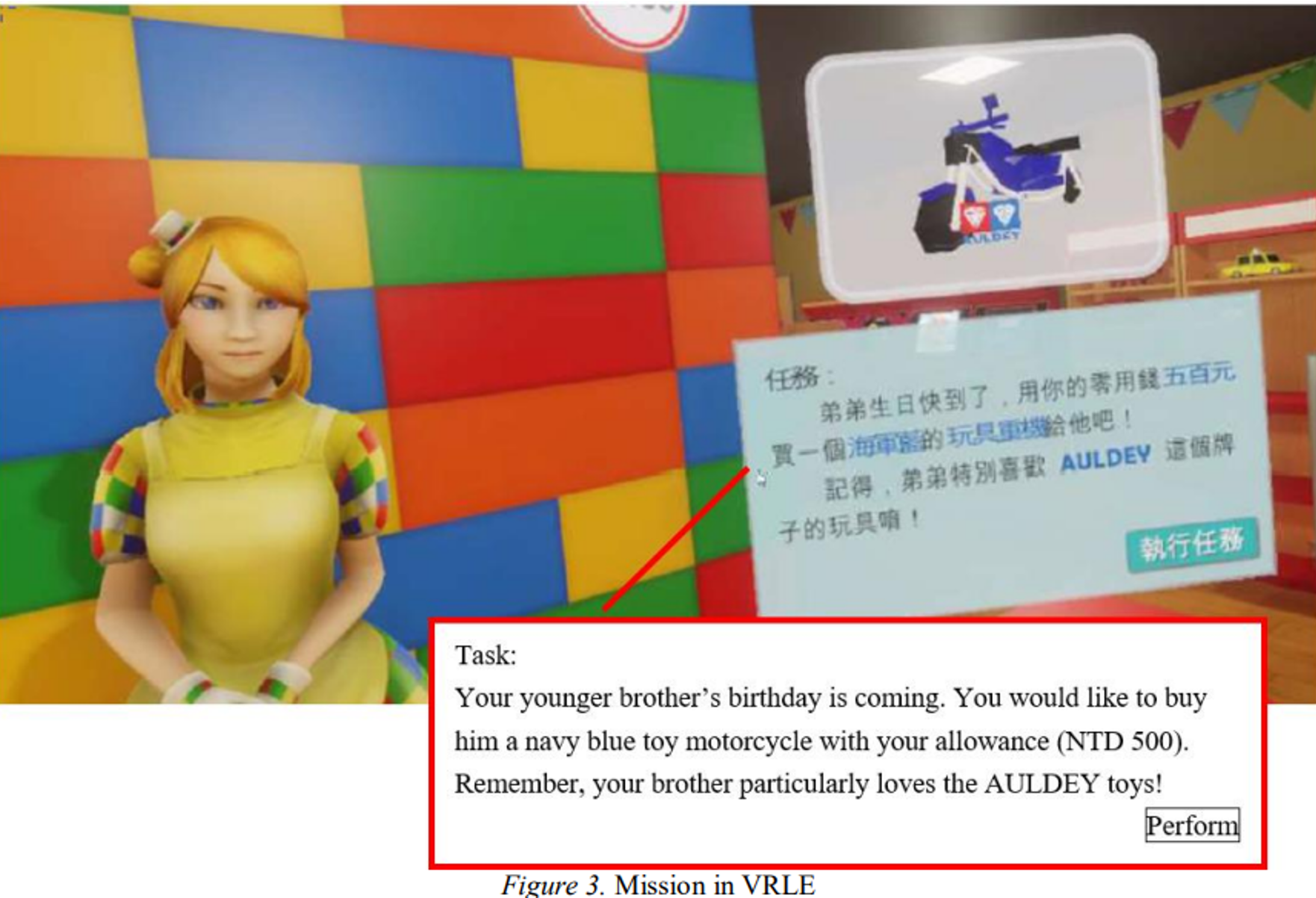

Case Study: “Virtual Reality Life English” (VRLE) for Junior High School Learners in Rural Taiwan

To address low English achievement and motivation among rural junior high school students in Taiwan, researchers developed Virtual Reality Life English (VRLE)—a 3D animation-based VR learning system using HTC VIVE and Kinect for immersive, full-body interaction.

Design: VRLE focused on task-based scenarios such as ordering food, asking for directions, and buying toys, allowing students to practice everyday English in simulated real-life settings.

Development: English instructors created level-appropriate scripts, which were turned into interactive 3D environments by a technical team using Unity and 3Ds MAX.

The system served as a complementary tool to enhance curriculum-based instruction and learner engagement.

The following is the findings of Yang, Lo, Hsieh, and Wu (2020).

RQ1: To what extent did VRLE enhance the communicative ability of low-achieving EFL learners?

A paired-samples t-test revealed a statistically significant improvement in students’ communicative performance after using VRLE:

- Pre-test mean: 60.56

- Post-test mean: 68.82

- Statistical significance: p < .001

- Inter-rater reliability: Krippendorff’s α = .86

These results indicate that VRLE had a substantial positive impact on the learners’ English-speaking ability.

RQ2: To what extent did VRLE affect learners’ sense of presence?

Data from the Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ) showed learners experienced a moderate to high sense of presence:

- Spatial presence: 5.31

- Overall presence: 5.27

- Caption-related presence: 4.48

- Involvement: 4.43

- Realness: 3.88

Key results:

- Students felt physically situated in the virtual space (high spatial presence).

- Captions helped with comprehension but reduced realism.

- Students were engaged, though some were distracted by real-world factors.

- The environment was perceived as realistic, though not identical to real life.

RQ3: What were learners’ overall perceptions of the VRLE system?

From interviews with eight students, four major themes emerged:

- Realism

- The VR environment felt immersive and lifelike, aided by free object interaction and native speaker voiceovers.

- Some students experienced physical discomfort or technical difficulties.

- Engagement

- Task realism increased focus and interest.

- However, headset cables and peer performance anxiety were noted as distractions.

- Captioning Preferences

- Caption-on: Supported understanding and reduced anxiety, especially for lower-level learners.

- Caption-off: Felt more authentic and encouraged active listening.

- Suggestions for Improvement

- Expand virtual space, add more interactive characters.

- Include a reward system (e.g., virtual currency).

- Provide in-world hints (e.g., posters).

- Display the learner’s own avatar/body for enhanced immersion.

Overall Summary

The VRLE system proved effective in improving the communicative skills of low-achieving EFL learners. It fostered immersion, task engagement, and real-world applicability. Learners responded positively to its features. The findings support VRLE as a promising tool in communicative language teaching (CLT), particularly in under-resourced educational settings.

The advantages of VR are evident; however, this article also highlights its drawbacks in practical teaching. More importantly, it addresses students’ reactions to the technology — all of which are crucial factors that must not be overlooked in the ongoing reform and development of VR-based education.

9. Teachers’ Perspectives on Using VR in Education

1. Curriculum Alignment

Teachers generally viewed VR as a tool that could be effectively integrated with existing curricula across various subjects. Studies showed that VR-supported lessons were often designed to align with national curriculum goals in subjects such as geography, science, mathematics, and social studies. For example, 360-degree VR helped meet geography learning outcomes (Maher & Buchanan, 2021), while immersive VR content was successfully incorporated into science lessons to meet national standards (Liu et al., 2020). Teachers emphasized the importance of aligning VR content with lesson objectives and learner needs (Khukalenko et al., 2022). In some cases, VR acted as both an amplifier of learning materials and a reorganizer of learning contexts (Rodríguez, Romero & Codina, 2021).

2. Concerns About Integration

Despite the potential benefits, teachers expressed concerns about several practical issues. These included costs, access to devices, and the need for reliable Wi-Fi connections. Some teachers found VR to be affordable due to the use of learners’ existing mobile devices (Patterson & Han, 2019), but others were worried about students without personal smartphones or the need to inform parents about device usage. Technical issues, such as inconsistent device compatibility and limited VR content, were also mentioned (Alalwan et al., 2020). Time constraints within regular class schedules further complicated implementation.

3. Perceptions of VR as an Effective Teaching Tool

Overall, teachers considered VR a valuable educational tool, particularly for teaching abstract concepts and increasing student engagement. It was associated with enhanced motivation, independent learning, and interest in STEM subjects (Alalwan et al., 2020; Hui et al., 2022). VR helped struggling learners become more engaged and encouraged a shift from traditional teaching to more interactive, inductive approaches. Teachers modified lesson plans to accommodate VR-based learning and observed improved classroom participation.

Professional development played a key role in successful implementation. Teachers who received training felt more confident in using VR and were more likely to integrate it into their teaching (Liu et al., 2020; Khukalenko et al., 2022). Those who used analytics platforms to track student behavior also gained deeper insight into learning processes (Maher & Buchanan, 2021).

4. Challenges Related to Students

Teachers highlighted concerns about students’ adaptation to VR. Some were uneasy about learners being distracted or accessing unrelated content, prompting the use of guided modes (Patterson & Han, 2019). Others questioned the effectiveness of VR for teaching specific subjects or worried about health risks, such as dizziness (Alalwan et al., 2020). While most students tolerated the experience well, teachers emphasized the need for adult supervision, especially when using headsets. There was also concern about students’ low technological literacy, suggesting a need for enhanced training in VR use (Alalwan et al., 2020).

5. Opportunities and Benefits for Learners

Teachers identified multiple benefits of VR for student learning. The technology encouraged active participation, creative thinking, and problem-solving. VR enabled learners to visualize and manipulate 2D and 3D shapes, develop spatial reasoning, and experience abstract concepts in concrete ways (Rodríguez, Romero & Codina, 2021). It also helped generate enthusiasm for learning and enriched class discussions. Some teachers observed improvements in learners’ ability to create, visualize, and express artistic and scientific ideas (Hui et al., 2022). Students found the VR environment intuitive and easy to use, and preservice teachers described the immersive experience as “feeling real,” indicating strong potential for learner engagement (Lin & Sumardani, 2023).